|

| Winston Churchill (highlighted) at the Sydney Street Siege |

In Victorian and Edwardian times there was another terrorist threat besides the Fenians - anarchists and revolutionaries.

In the 1840's movements for democracy swept Europe - Italy, France, and Poland stood on the brink of revolution and thinkers and activists encouraged uprisings. Many of Europe’s revolutionaries and anarchists ended up in exile in comparatively liberal Britain: it became the home for other people’s ‘terrorists’.

The Greenwich Observatory Bomb

On 16 February 1894, a bomb exploded less than fifty yards from the Royal Observatory at Greenwich Park. Some passing schoolboys were first on the scene, followed by a park ranger. They found a man kneeling and bleeding but still able to talk. The man was taken to a nearby hospital, where he died within the hour. He was soon identifed as 26 year old Martial Bourdin, born in France, now living in London. A large amount of money was found on his body, suggesting he intending to flee to France after planting the bomb.

Scotland Yard quickly traced the dead man to the Autonomie Club, the headquarters for anarchists and revolutionaries in exile from across Europe. The Club had recently issued a manifesto which proclaimed, "In a struggle like this we hold that all means - however desperate - are justifiable." The incident stunned Britons who had felt themselves safe from the wave of anarchist violence that was sweeping the continent. Many members of the club were arrested, then released without charge and deported.

+++++++

Latvian Revolutionaries

Many Latvians had fled to London following the suppression of the revolt in their country in 1905. There they continued revolutionary and propagandist activity, staying in funds largely through "expropriations," their euphemism for what we today call "ripping off."

The Tottenham Outrage

On 23 January 1909, two Latvian refugees of London's East End assaulted a messenger carrying the wages for a local rubber factory. During the struggle shots were fired and overheard at a nearby police station. A police chase ensued, but as the use of firearms by police or criminals was then virtually unknown, the armed Latvians had an advantage. The police armed themselves, and ran the criminals to the ground after a six-mile chase in which two people were killed and 27 injured.

The Houndsditch Murders

On 16 December 1910, a gang of Latvian refugees attempted to break into the rear of a jeweller's shop at 119 Houndsditch, working from adjacent buildings. A shopkeeper heard their hammering, and informed the City of London Police. Nine unarmed officers went to investigate. The anarchists started shooting, two police officers were killed, and another three injured. An intense search followed, and a number of the gang and their associates were soon arrested.

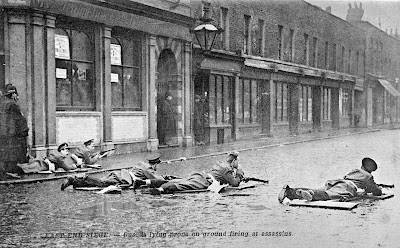

Sidney Street Siege

An informant told police that two or three of the Latvian gang were hiding in Mrs Betsy Gershon's flat in 100 Sidney Street, east London. On 3 January 1911, two hundred Met and City Police officers cordoned off the area and evacuated the residents. The gunmen had removed Mrs Gershon's skirt and shoes to prevent her from leaving the building, but she was permitted to go downstairs, where the police managed to rescue her.

The police were armed with bulldog revolvers, shotguns and rifles fitted with .22 Morris-tube barrels for use on a minature range, but these proved completely inadequate for flushing out the gunmen, whose Mauser pistols were capable of rapid and deadly fire.

|

| Scots Guards at the Sidney Street Siege |

Home Secretary Winston Churchill was asked for permission to send for troops. He granted permission and twenty one volunteer marksmen of the Scots Guards arrived from the Tower of London. Three were placed on the top floor of a nearby building, from which they could fire accurately into the second storey and attic windows from which the gunmen had been shooting. The gunmen were driven down to the lower floors where they came under fire from more guardsmen positioned in houses across the street.

When Churchill couldn't get any news about the siege from the Home Office, he decided to go there and see for himself (see photo at the top). He arrived just before midday, and since he was the most senior person there he felt responsible, so he decided to assume personal command of operations. He decided heavier artillery was needed. A bullet passed through Mr Churchill's top hat, coming within inches of killing him. Just as the field artillery piece arrived, smoke was observed rising from the building, and one of the gunmen emerged from a window, then fell back suddenly, almost certainly having been shot. The rate of fire then slowed considerably.

|

| Detectives inspect the house at 100 Sidney Street at the conclusion of the siege |

The building burst into flames, and although the Fire Brigade arrived they were forbidden by the police to extinguish the blaze. The Fire Brigade argued with the police, but Churchill too forbade them from approaching the house. He asked them instead to stand by should the fire threaten to spread to adjacent buildings. The last shots from 100 Sidney Street were heard at 2.10pm. Fire gutted the building, and the roof and upper floors caved in. Firemen were at work to prevent damage to other buildings when a wall collapsed, burying five people, one of whom died in hospital. The bodies of two anarchists were found inside the house, one on the first floor where he had been shot, and the other on the ground floor where he had been overcome by smoke.

Part I of this article series - The Fenians

2 comments:

Brilliant post, very well done.

Thanks for visiting and commenting!

Post a Comment